In past columns, I’ve reviewed how food politics influence federal nutrition guidelines and programs like “Let’s Move!” and “Drink Up!”. Alas, politics reaches far and wide, even throughout academia and research. The food industry is well aware of increased scrutiny from nutrition and public health advocates, and it’s cooked up one ingenious way to minimize criticism of its products: sponsored research.

In past columns, I’ve reviewed how food politics influence federal nutrition guidelines and programs like “Let’s Move!” and “Drink Up!”. Alas, politics reaches far and wide, even throughout academia and research. The food industry is well aware of increased scrutiny from nutrition and public health advocates, and it’s cooked up one ingenious way to minimize criticism of its products: sponsored research.

As food politics guru Dr. Marion Nestle wrote on her blog last year:

“In my opinion, agriculture, food, nutrition, and health professionals should dismiss industry- sponsored research out of hand, and journals should not accept industry-sponsored papers. There is only one reason for food companies to sponsor research—so they can use the results in their own interests.

Sponsorship perverts science. Sponsored research is not about seeking truth or adding to public knowledge. It is about obtaining evidence to defend or sell the sponsor’s product, to undermine research that might suggest that a product is unhealthy, to head off regulation, and to allow the product to be marketed with health claims.

This is precisely the motivation behind many food companies’ institutes, like Coca-Cola’s Beverage Institute for Health and Wellness and General Mills’ Bell Institute. On the one hand, these institutes serve as a way to co-opt science and frame the discussion. Additionally, they serve as a great way to distract from troublesome ingredients. General Mills’ Bell Institute, for example, puts out plenty of materials on whole grains, but conveniently doesn’t address the fact that many of its cereals are nutritionally empty (their vitamin and mineral content is simply tacked on during processing; that is to say, these cereals are so processed that without fortified nutrients they would offer very little nutrition).

For years, public health and nutrition advocates raised their concerns about sponsored research and the propensity with which it spins results in a way to make Big Food’s hyper-processed foods seem harmless. We are finally starting to have proof that these concerns are warranted.

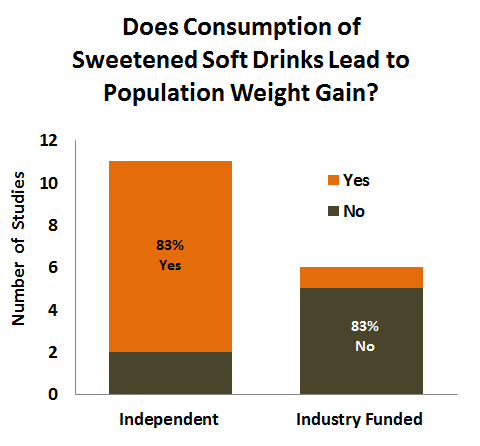

Consider the question of whether soft drink consumption is tied to weight gain. The soda industry – largely through its front group, the American Beverage Association – is quick to tell you that “there is no evidence” that that claim is true. Finally, though, we can point to science that proves that claim wrong.

Earlier this month, the Public Library of Science Medicine published a research article titled “Financial Conflicts of Interest and Reporting Bias Regarding the Association between Sugar-Sweetened Beverages and Weight Gain: A Systematic Review of Systematic Reviews.”

Its authors found that “systematic reviews that reported financial conflicts of interest or sponsorship from food or drink companies were more likely to reach a conclusion of no positive association between SSB consumption and weight gain than reviews that reported having no conflicts of interest.” More specifically, “systematic reviews with financial conflicts of interest were five times more likely to present a conclusion of no positive association between SSB consumption and obesity than those without them.”

They also point out that “the interests of the food industry (increased sales of their products) are very different from those of most researchers (the honest pursuit of knowledge),” and suggest that “clear guidelines and principles (for example, sponsors should sign contracts that state that they will not be involved in the interpretation of results) need to be established to avoid dangerous conflicts of interest.”

If you’re more of a visual person, this graphic makes the problem very clear.

It’s certainly information to keep in mind the next time an industry spokesperson tells you that, conveniently, science is on their side (and theirs only). What is most disturbing is that federal funding for nutrition research – which was never that ample to begin with – has taken a hard blow during the current economic climate. This has given the food industry a perfect opportunity to swoop in and provide funding.

Is every researcher who accepts money from the food industry corrupt? No. However, we need to take a step back and ask a very simple question: “Would industry ever publish a study that linked its products to negative health effects?”. In fact, I challenge you to find one industry-funded study that does precisely that (i.e.: research funded by Coca-Cola which shows a link between soda intake and increased risk of developing kidney stones).

Remember, too, that while scientific data is objective, the way it is framed and presented is highly subjective. Case in point: in 2009, Kellogg’s made the claim that Frosted Mini Wheats helped children perform better in school. What they neglected to tell the media and the general public was that they came to that conclusion by creating a study with two groups: one group ate Frosted Mini Wheats for breakfast; the other didn’t eat breakfast at all. Fortunately, Kellogg’s did not get off the hook; it agreed to a $4 million settlement in a class-action lawsuit over deceptive marketing claims.

Whenever you come across a research study – whether it be in the media or an actual research journal – always ask yourself two important questions: “who?” and “why?”. While skepticism is just as limiting as naivety, it is vital to develop and use critical thinking, particularly when it comes to an industry that is so adept at employing spin.

Andy Bellatti, MS, RD is a Las Vegas-based nutritionist with a plant-centric and whole-food focus. His work has been published in Grist, The Huffington Post, Today’s Dietitian, Food Safety News, and Civil Eats, among others. He is just as passionate about healthful eating as he is about food politics, deceptive Big Food marketing, and issues of sustainability, animal welfare, and social justice in our food system. He is the creator of the Small Bites blog (which, though now closed, has almost 2,000 archived posts). You can also follow Andy on Twitter and Facebook.